Finance systems are just Tetris pieces. The real tool is the information. And it takes a significant amount of research and business acumen to ensure that information is accurate and flowing correctly.

Further, if you want that information to lead to transformation—to use it to help various functional leaders be more effective—you need everyone to realize that their systems aren’t the ultimate truth. And help them see that they are all part of a larger collection of systems.

This is the process I’ve developed to lead teams to that awareness in my first 100 days. I want the executive team and our directors to all understand that we’re trying to achieve a unified view. That doesn’t mean scolding anyone, but rather trying to deeply understand their work.

This article is part of a series where Everest invites domain experts from manufacturing, supply chain, analytics, and operations to share their change management wisdom.

1. First, observe everyone in the course of regular operations

Economists often talk about the world in terms of people who rationally assess tradeoffs, and in my experience, they don’t really exist. People aren’t as money-motivated as we often think. They accept all sorts of inefficiencies at work and don’t realize when they get in other people’s way. In my first month, I look to understand where that’s happening.

I speak to everyone. I observe how people are interacting amongst themselves. I visit the offices, walk the plant floors, tour the warehouses, try to touch every site of labor. I identify and get access to all the important databases, and I start to crunch the numbers on how all these different parts of the business are working or not working with each other. I diagram on a whiteboard those various information flows. By the end, I hope to know people in each department in such detail that I know who’s getting divorced, who has a new boyfriend, what concert they took their kids to.

Each different discipline like legal, HR, and marketing all tend to speak their own languages, so I pay attention to where there are mistranslations happening. For example, marketing reporting new pipeline generated that doesn’t accord with what’s in the ERP.

Further, I’ve noticed that in any company that manufactures its own goods, you essentially have two separate companies: the office worker side and the labor side. Labor often feels at odds with the business. Each tends to generate very different information and share it incompletely.

This month of observation tells me:

Where communication occurs.

Where miscommunication occurs.

What numbers are being generated.

How those numbers are being collected.

Any information loss or conflicts.

What levers we have to change those numbers.

2. Second, compare the data

I compare the numbers in the three primary systems: ERP, CRM, and manufacturing. Plus any other relevant databases, like specialized ERPs, Excel tools, and so on. In particular, I look at the number of customers or contracts signed in CRM vs the ERP to see if they match. Did sales’ entries make it into the ERP? If so, how do things differ? Even if you account for the number of contracts, things will disagree. Information doesn't flow linearly in something as simple as an invoice. Ask HR how many employees there are and how many positions the company has, and probably, we will have to apply quantum computing to make numbers match. Ask legal about exposure on ongoing disputes and we will get a detailed explanation of how many consultants are needed and a very big ballpark figure of cost with no answer to the original question. Ask IT for an inventory of computers owned or leased by the company and wait, and wait, and wait.

If all the above numbers are the same, we’re in great shape, but in my experience, that has never been the case. This highlights where the information flows and processes are broken; where people are not talking or where someone’s just relying on a forecast summary someone shares in an email update without checking the actual spreadsheet.

3. Third, present the numbers

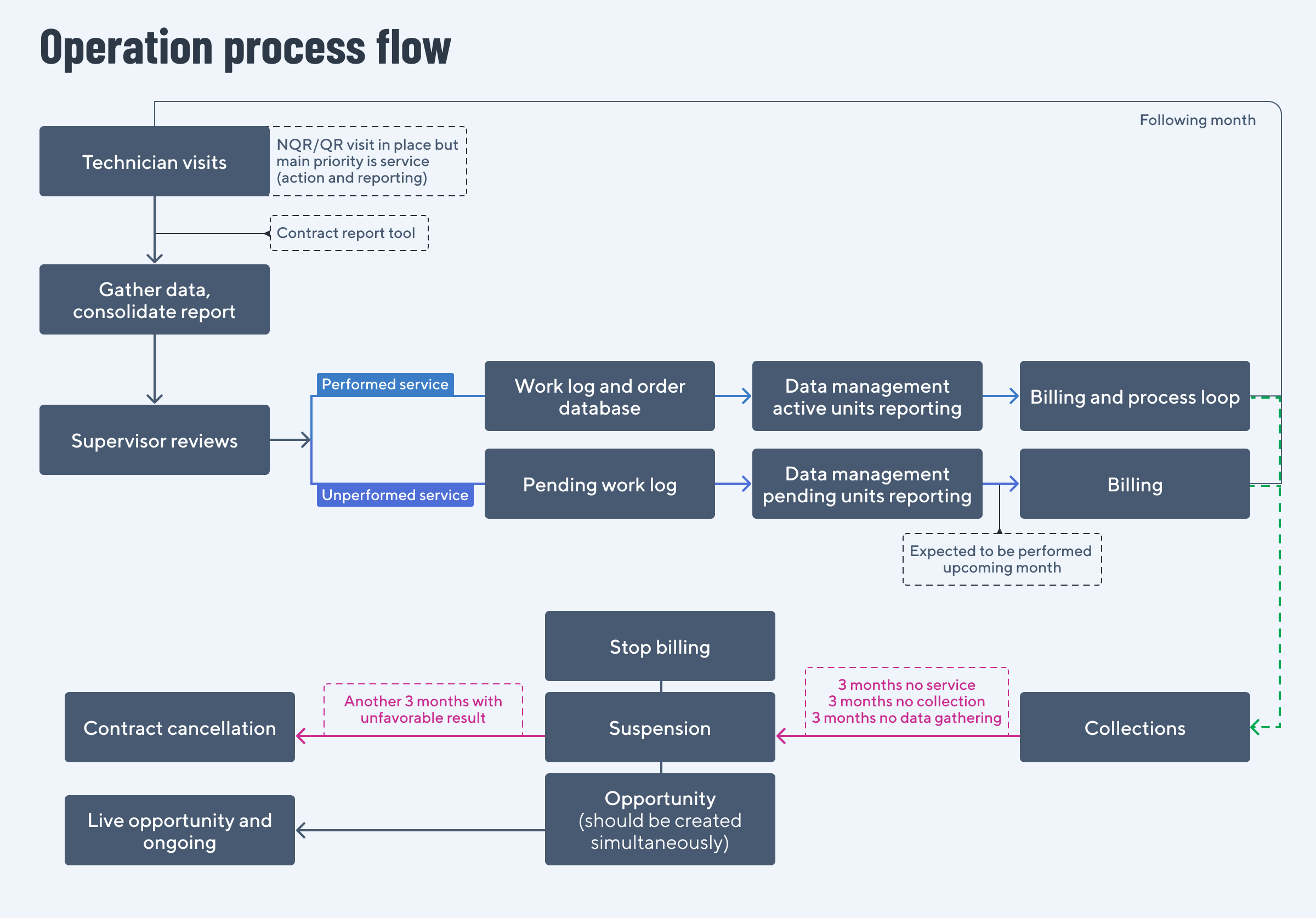

After my three months of research, I sit down with the various decision-makers and show them the analysis. I say, “I don’t know your business like you do, but I do know numbers. And the numbers are telling me this. This is how the information flows and this is where it gets lost.” I present a flow chart that ends in the P&L, or with the area where it's disturbing the process.

It is important to phrase this conversation lightly: “I don’t know what happened to the numbers here, can you help me with this?” It’s important not to blame or imply that anyone messed something up. I want to boost them up and invite them to help solve the problem. Showing that you’ve tried to understand their process goes a long way to earning their help.

Then I show the consequences of those numbers. “This is affecting that, and here’s the organizational side effects.” People will think they knew the numbers. But they weren’t taking into account taxes and exchange rates, and when they see the diagram, they say, “Ahh.” Maybe the sales team finally realizes the financial implications to sending contacts in a different currency in new territory you hadn’t planned for, and losing 30 cents on every dollar. Or the procurement team realizes that by holding inventory for as long as you are in U.S. warehouses, you’re being taxed differently.

Very often, people react and say, “Well maybe this process should be like this or that,” and now they’re helping you solve their own issues. And they are seeing—in that meeting—why it’s so important for all of them to talk to each other. And they understand what it is I’m there to do.

With that foundational understanding, you can start to make changes

The downside to this process is that it, of course, takes time and analysis. Nobody wants to hire an executive and wait 100 days to hear their plan. But often, people didn’t know why they were hiring a finance executive other than that they needed more certainty, rigor, performance, and compliance, and through this process, I can create a very good roadmap. I start with understanding those information flows and systems, so I can then apply an understanding of the business to not just ask others to hit numbers, but to suggest ways we can get there.